When are the European Elections?

Elections for the European Parliament will be held 23-26 May 2019 in 27 EU member states. We assume – for the moment – that the UK will have left the EU and will not participate in these elections.

How are the European Elections run?

The elections are organized nationally, with national and sometimes regional lists of candidates according to a proportional representation system. In some countries, national or regional elections are held on the same day (e.g. Belgium), in others, national elections will take place a few weeks before (e.g. Spain, Finland).

What will be the key themes?

The key topics in election campaigns will differ from one member state to another, reflecting national political priorities. However, the overarching common theme across all member states will be a fundamental choice between pro-EU parties striving towards further EU integration and those in favour of a return to more sovereign national decision making. The outcome will shape the future of Europe, at least for the next 5 years.

What is the impact of Brexit on the European Parliament?

Following Brexit, all 72 UK MEPs will leave the European Parliament. So the total number of MEPs elected will change. Some member states will see their number of MEPs increase slightly, creating a Parliament composed of 705 MEPS instead of the current 751. Some political groups will be more affected by the departure of the UK’s MEPs than others, as we discuss below.

How will the European Parliament change?

In Parliament, numbers decide. So what really matters for the future of EU policy making is the majority political groupings that emerge.

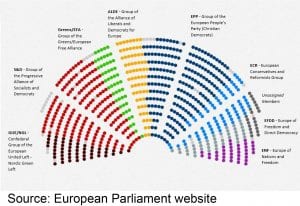

Once elected, MEPs organize themselves into political groups according to their broad political leanings. Groups must be composed of at least 25 MEPs from at least 7 member states.

In the current Parliament, there are 8 political Groups, none of which are big enough to carry a majority on their own – so they tend to form majority coalitions to carry votes.

For the duration of the current Parliament term, a stable coalition encompassing the EPP, S&D and ALDE has held firm, supporting the political appointment and programme of Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and passing 80-90% of all legislation proposed by the Commission, be it with amendments. The stability of the EPP, S&D, ALDE coalition has provided a degree of predictability within the European Parliament and has allowed the Commission to test its ideas before publishing a formal proposal, leading to more efficient law-making.

Whether the new European parliament will have such a stable coalition after the European elections remains to be seen.

How will the political groups change?

The EPP may lose some seats, but is expected to remain the largest political Group. It is unaffected by Brexit as it contains no UK MEPs.

The S&D is set to lose seats, with the departure of its UK Labour members and the poor performance of socialist parties in recent elections in France, Italy and Poland.

The ECR, currently home to UK Conservatives, could change fundamentally, with the Polish PiS possibly taking centre stage.

EFDD, currently home to UKIP, will lose half of its members post Brexit and could implode entirely.

The liberal ALDE Group is set to change with the rumoured arrival of MEPs from Macron’s La République En Marche party that did not exist at the time of the last European election. There remains uncertainty around how the more traditional liberal parties will fare, especially those less enthusiastic about about further European integration, like the Dutch VVD or the German FDP. Some believe that a new group may emerge to gather pro-EU centrist parties.

What impact could the rise of populism in Europe have?

Commentators speculate that the elections could see a rise of populist euro-sceptic parties across Europe, from both the left and right ends of the political spectrum – Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, La France insoumise, Germany’s AfD or Die Linke, Italy’s Lega, Spain’s Vox, extremist parties in Central Europe, and Geert Wilders’ party in the Netherlands. Success at the polls for these groups could lead to a gradual unraveling of the EU institutions’ power, or at least a change of emphasis away from EU policy towards national concerns such as drastically limiting free movement and immigration, so the opinions claim.

However most predict these parties obtaining a maximum of 25%-30% of seats, not enough to form an anti-EU populist majority. In this scenario, the populists could disrupt debate to attract media attention, using the European Parliament as a platform for their national agenda. But they will not materially impact EU policy or legislation – in Parliament the majority decides, not the vocal minority.

How will the new political groups create a majority coalition?

So the key question is whether the EPP, still the largest group, will build a coalition through alliances to the left (with S&D, ALDE & Greens) or to the right, (e.g. with a reformed ECR) – or whether they will find it impossible to create any kind of stable coalition at all.

In the absence of a stable majority, coalitions would be ad hoc and unpredictable, changing with every vote. This could lead to a less than coherent voting pattern on policy and legislation – strict climate rules supported by a majority including Greens one week, and strict migration policies supported by a majority of right wing parties the next. Alternatively, workable majorities could prove elusive, leading to frustration and deadlock.

What will happen after the elections?

The immediate role of the new Parliament will be to endorse a new Commission President proposed by the heads of government in the Council – and his or her political programme for 2019 – 2024. The political programme is negotiated with the majority coalition in the Parliament giving the MEPs in that coalition significant influence over the future direction of EU policy for the forthcoming term. A left leaning parliamentary majority including the Greens would likely lead to a greater focus on curbing climate change and tax evasion, while a majority along the classic EPP + S&D + ALDE + ECR lines would seek to prioritise the economy and security.

The Parliament will also hold a series of hearings to scrutinize all candidate European Commissioners, usually rejecting one or several candidates in the process. Again, the composition of the coalition majority plays a role here.

How will the elections impact business?

The next cohort of MEPs, and their political groupings, will shape the policy priorities of the Commission for the next 5 years and determine whether the EU’s internal market, social and fiscal initiatives, trade policies, … will be supported or frustrated.

A workable, stable coalition consisting of essentially pro-EU parties would lead to predictable voting patterns, based on negotiated compromise. A strong representation of populist parties may render building a stable coalition difficult or impossible.

The composition of the majority coalition will determine the intensity of lobbying activities deployed. In the absence of a strong coalition, the Parliament will be governed by unpredictable and ever shifting alliances, generating more intensive lobbying efforts by those seeking to influence voting results. In this environment, it may be easier to frustrate than advance legislation.