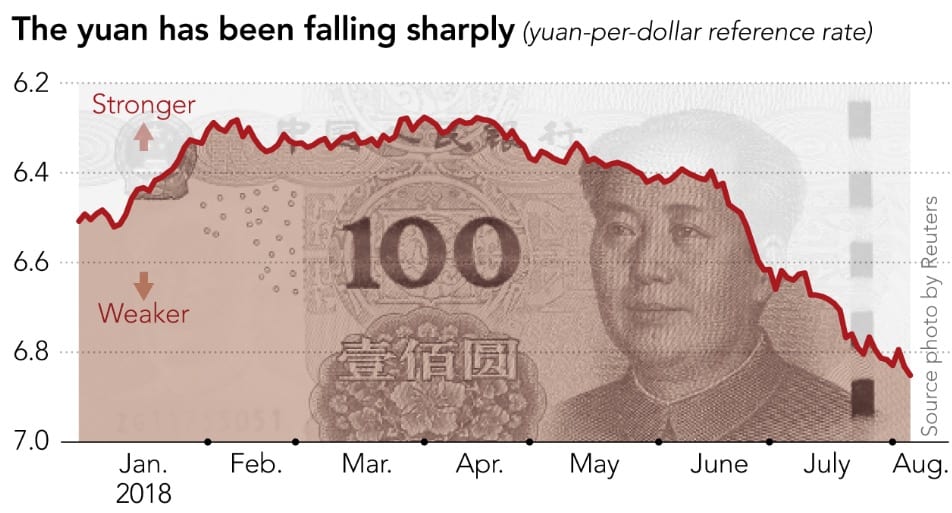

Consequently, the tariffs are not having the intended political effect. In June, the U.S. trade deficit grew 7 percent to $46.3 billion, the first increase in four months. The trade deficit is on track to be the largest in a decade thanks to an unabated American appetite for Chinese goods as well as the weaker yuan. Compared to a year earlier, Chinese exports rose 12.2 percent, beating forecasts of a 10-percent increase and June’s 11.2-percent gain.

That all this is happening is not what is being debated. The issue is what is causing the yuan’s slide and what this means for policymakers who are trying to achieve the exact opposite of the current outcomes. Some economists argue that the yuan’s slide is not caused by the tariffs but the threat of a trade war. That threat of worse to come, they say, is the main driver of systemic risk across currency markets. Others, citing the recent increases in China’s foreign-exchange reserves that now exceed $3.1 trillion, accuse China of currency manipulation. Still others say that China is guilty not of weakening its currency but of doing nothing to stop it.

And then there’s Sen. Rob Portman, who says that China is unclear about U.S. intentions amid stalled bilateral talks, rendering meaningless any accusations of currency manipulation in response to U.S. tariffs. What the U.S. and China currently have is in effect a cold trade war, where neither side is clear about the other’s intentions. The pain, which President Trump is counting on to force a better trade deal with China, is largely mitigated by the yuan’s devaluation.

What we’ve got here is failure to communicate. Indeed, the U.S. and China are only talking about talking as negotiations are on hold. And as the president predicted, economic pain is what is needed to break this political stalemate. Unfortunately, his voters are the most likely to feel it. Since President Trump took office, job growth has been concentrated in Democratic strongholds, with 58.5 percent of new jobs in 2018 being created in counties that backed Hillary Clinton in 2016 while much of Trump country is actually losing jobs, according to the Associated Press. The AP found that more than a third — 35.4 percent — of Trump counties have seen a net loss of jobs this year.

This week the Chinese Ministry of Commerce announced that it will levy a retaliatory 25-percent tariff on $16 billion worth of U.S. goods, including crude oil and cars. Gas is about to get more expensive in the U.S., and this will cause economic pain in President Trump’s political backyard to those Americans for whom a full tank of gas is an expensive necessity. These are voters who are not feeling the benefits of economic growth and who are currently keeping the president’s approval ratings from falling into the 30s. If President Trump becomes more unpopular, it could put the Senate into play, and this could force congressional action on trade or push President Trump to the negotiating table with China.

The president’s right in that pain will force concessions — unfortunately for him, he’s the most likely policymaker to feel it.

***

|