Most observers, myself included, thought getting Canada to join the new NAFTA before last weekend’s deadline was a long shot. But as difficult as it was to keep Canada in the fold — and as good as that news is — now comes the hard part. Soon the renamed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) will require legislative approval in all three countries. No one expects this to be much of a problem in Canada or in Mexico. But early next year, USMCA will arrive before the new U.S. Congress, which is when the task at hand moves from private negotiations to public salesmanship.

Selling Canada’s Prime Minister on the deal was the easy part. Winning over the American public will be the hard part, as it was in passing NAFTA in the ’90s. It was, safe to say, an uphill fight. An NBC-Wall Street Journal poll taken just before the 1992 election showed that 40 percent were either unsure or did not have an opinion on NAFTA, 27 percent supported NAFTA, and 34 percent opposed NAFTA. For a year, a coordinated effort explained NAFTA’s benefits, resulting a plurality of the country supporting the trade agreement.

Back then, the key to passing NAFTA was getting enough support from Democrats, who controlled Congress at the time. The core of opposition to NAFTA was led by labor unions and House Majority Leader Richard Gephardt and House Majority Whip David Bonior. Even with President Bill Clinton’s staunch support, only a minority of Democrats in the House voted with most of the Republicans to pass it, showing, I suppose, what can be accomplished when both parties rise above differences to work together.

If Democrats win control of the House of Representatives as most non-partisan analysts expect, Republican Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa says that the Senate will vote on USMCA in the lame duck session between the election and the swearing in of the new Congress right after the New Year. Voting on the trade agreement then is not a sure thing, however. Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn of Texas, who counts votes in the Senate for the Republicans, isn’t on board with that plan yet.

More significant is the strict schedule required under Trade Promotion Authority, or TPA, which outlines what happens next for the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement:

- The President can’t sign USMCA until 60 days after the trade agreement is released, which in this case is Nov. 30, or almost a month after the election, dramatically shortening the window in the lame duck congress.

- 60 days after the President signs USCMA, a list of required changes in law is due. And 105 days after the agreement is inked, an International Trade Commission report on the economic impact of the deal is due. These things can happen at the same time.

- After the required changes and the ITC report are released, the administration can send implementing language to Congress, which starts the congressional process. There’s no deadline for that. What is likely to happen is that the administration will submit the legislation when it has the votes to pass it.

- Congress then can take 90 legislative days to pass the trade deal.

- Congress can only vote up or down on the trade agreement. No amendments are allowed.

Add all those days together and it’s unlikely that the lame duck Congress will get to vote on the trade deal, which means President Trump will also need to win over Democratic votes to pass a trade agreement. The initial read is that this might be almost impossible. If Bill Clinton couldn’t get most Democrats to vote for NAFTA, it might be too much to expect President Trump to do so, especially when it means giving him a major legislative win at the onset of his re-election campaign.

Despite changes to NAFTA that benefit U.S. auto workers, the United Auto Workers are reserving judgment until they win concessions that the USCMA will strengthen the labor enforcement provisions. If, as some have said, USCMA merely updates and does not overhaul NAFTA to provide stronger worker protections, organized labor is unlikely to get on board. Keep in mind, an August Pew Research survey by found that just 40 percent of union households approved of Trump’s job performance while 58 percent disapproved.

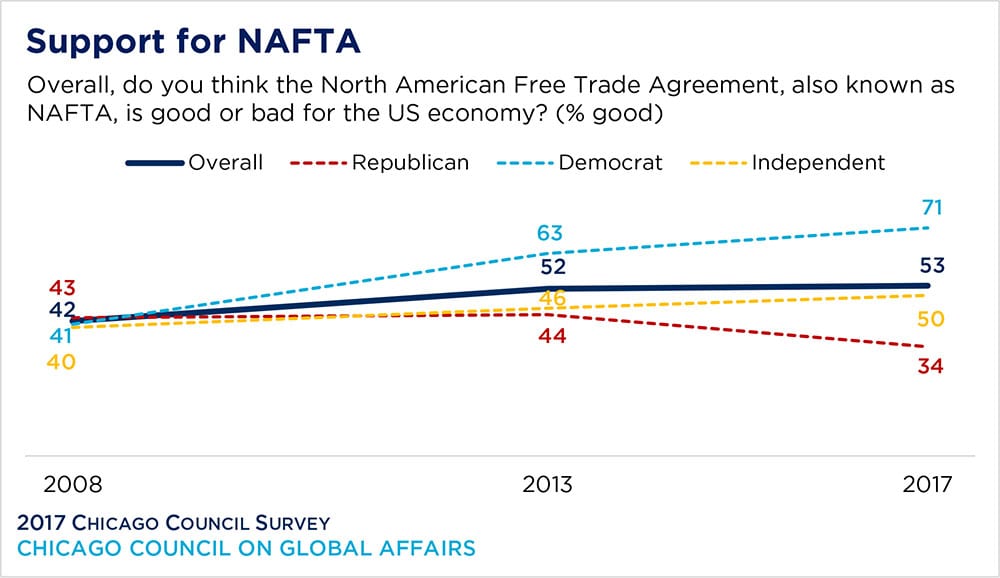

I actually think the President might have a better chance than people think in getting Democrats on board. First, renegotiating NAFTA is hardly a radical idea among Democrats — it was endorsed by both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama in 2008. Second, the Democratic Party has come a long way on trade in general and NAFTA in particular. Since Obama was elected, Democrats’ support for NAFTA has risen from 41 percent to 71 percent, more than twice the share of Republicans who currently back NAFTA. Finally, many, if not dozens, of the newly elected Democrats will come from districts that Trump won in 2016. The President would be asking Democrats to do something they essentially agree with, and if they do vote for USMCA congressional Democrats would show voters in competitive districts that they can work across the aisle to accomplish big things.

There are many issues to sort out before the revised trade agreement reaches Congress: There could be a devil hiding in USMCA’s details that we don’t know about yet, and other considerations unrelated to trade could interrupt its fast-tracked approval process. (See below.) Whether the President succeeds, though, depends on his ability to sell this deal to congressional Democrats and, ultimately, the public.